22 May|Chicago Tribune – If you have a faulty heart valve and decide to get it replaced, a surgeon will implant an artificial one that has undergone rigorous examination by the Food and Drug Administration.

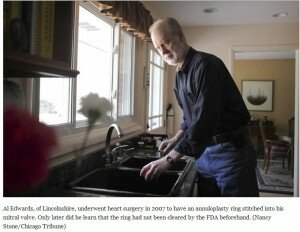

by Jason Grotto & Deborah L. Shelton Chicago TribuneBut if you choose the option recommended for most patients — repairing your valve with an annuloplasty ring — there are no such guarantees, even though both devices are permanently stitched into the heart and considered life-sustaining.

That’s because, a decade ago, the FDA downgraded the regulatory class of the rings. Instead of being grouped with heart valves and implantable pacemakers, annuloplasty rings were put into a class with most catheters, sutures and hearing aids, which allows the medical device industry to gain approval for new rings without clinical studies.

That’s because, a decade ago, the FDA downgraded the regulatory class of the rings. Instead of being grouped with heart valves and implantable pacemakers, annuloplasty rings were put into a class with most catheters, sutures and hearing aids, which allows the medical device industry to gain approval for new rings without clinical studies.

“It’s absolutely ridiculous. How could something that is permanently implanted in the heart be regulated this way?” said Diana Zuckerman, president of the National Research Center for Women & Families, a think tank that has fought for stricter oversight of medical devices. “The first question is: Who petitioned this change and what financial interest did they have?”

The answer, buried in federal records: the Advanced Medical Technology Association, or AdvaMed, which represents medical device companies.

A Tribune investigation found that the FDA rubber-stamped the group’s petition, allowing the invasive devices to make their way into the hearts of thousands of patients with virtually no scrutiny.

Today, annuloplasty rings have had more deaths associated with them during the past five years than any other device in their class, according to a Tribune analysis of FDA data on adverse events. Although there are many flaws in the way the FDA gathers its data and there is no way to tell if the deaths are directly related to the rings’ performance, the analysis raises questions about whether the agency erred in reclassifying the device.

The newspaper’s findings come amid a heated debate over the FDA’s regulation of the $100 billion-a-year medical device industry.

Despite reports of illnesses, injuries and deaths linked to faulty hip and knee implants, defibrillators, and other products, new devices continue to receive far less FDA scrutiny than new drugs, and patients often are left in the dark about safety issues. The Institute of Medicine is slated to release a study this summer about how devices like the rings are cleared for use, and the FDA is expected to rewrite some of its rules soon after.

Since annuloplasty rings were reclassified, companies have introduced dozens of new models that fetch higher average prices than older ones, without having to undergo the expense or time of clinical trials. By contrast, pharmaceutical companies must fund extensive research before new drugs are approved.

The regulatory change also paved the way for at least two models of the heart rings to be implanted in more than 700 patients without clearance from the agency. In fact, the FDA didn’t even know the rings existed.

Edwards Lifesciences, the California-based company that manufactured the devices, didn’t submit them to the FDA for clearance, later arguing it didn’t have to because the rings were slight tweaks of products that already had been cleared.

Yet the Tribune found that the company also filed patent applications for one of the rings, listing dozens of ways in which it was different than existing devices.

The agency ultimately decided that Edwards should have applied for clearance before selling them. But it did nothing to punish the company, which has seen its net income rise by 70 percent during the last three years to $218 million, according to filings with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.

Edwards declined to comment on the newspaper’s findings, saying through a representative that the company “followed FDA’s guidance” when it sold the rings and resolved the issue “more than two years ago.”

The rings are reclassified

When medical device laws were first put on the books in 1976, panels of medical experts placed every device on the market into one of three classes. Annuloplasty rings were in the highest-risk class, known as Class III, because “the device is implanted and life sustaining.”

The FDA was supposed to write regulations outlining what manufacturers must do to gain premarket approval, or PMA, for each Class III device. In the meantime, Class III devices on the market before the laws were enacted could be sold through the less rigorous Class II process, known as 510k.

That had huge implications for manufacturers. Going through a PMA costs hundreds of thousands of dollars and can take years, but the 510k process can be completed in a few months and costs companies as little as a few thousand dollars.